By Elliott Brack

Editor and Publisher, GwinnettForum

MARCH 20, 2020 | Many of the precautions our medical community is taking in the 2020 coronavirus pandemic stem from the reaction in American cities during the influenza pandemic more than a hundred years ago, in 1918.

The world-wide spread of the flu came as soldiers returned home from the trench warfare of the first Great War. On the war front in the trenches, living conditions were terrible, with rampant sickness going on for nearly two years. Many of the doughboys, returning to their homes around the world, did not have the flu, but were nevertheless carriers. That meant that the whole world was impacted by this terrible bug.

The world-wide spread of the flu came as soldiers returned home from the trench warfare of the first Great War. On the war front in the trenches, living conditions were terrible, with rampant sickness going on for nearly two years. Many of the doughboys, returning to their homes around the world, did not have the flu, but were nevertheless carriers. That meant that the whole world was impacted by this terrible bug.

When it was all over, the sickness (it was called the Spanish flu) killed an estimated 675,000 Americans and a staggering 20 to 50 million people worldwide. (The 1918 Spanish flu got its name after King Alfonso of Spain, 32, fell ill that May, but did not die of the disease.)

Decades later, in 2007, health officials in the United States undertook a study to find how certain areas of the country did better with that widespread flu than did other areas. The two cities chosen for the study were St. Louis and Philadelphia. We heard about this from a news report on National Public Radio.

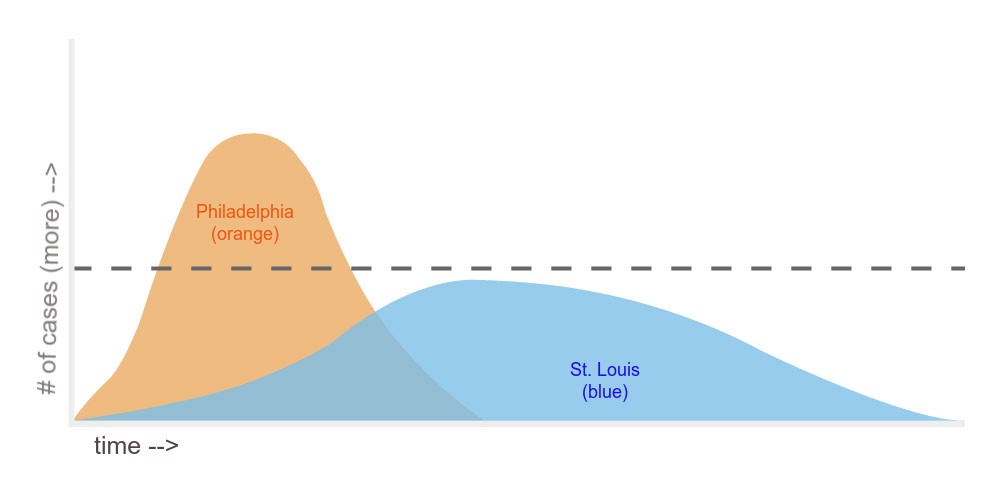

The study found that the faster authorities moved to implement the kinds of social distancing measures designed to slow the transmission of disease, the more lives were saved.

In Philadelphia, city officials ignored warnings from infectious disease experts that the flu was already circulating in their community. Instead, they moved forward with a massive parade in support of World War I bonds that brought hundreds of thousands of people together. Within three days, thousands of people around the Philadelphia region started to die. Within six months, about 16,000 people had died.

When a flu outbreak at a nearby military barracks first spread into the St. Louis civilian population, the city wasted no time closing the schools, shuttering movie theaters and pool halls, and banning all public gatherings. When infections swelled as expected, thousands of sick residents were treated at home by a network of volunteer nurses.

In St. Louis, city officials approached the problem differently. Within two days of the first reported cases, the city quickly moved to social isolation strategies. As a result, St. Louis suffered just one-eighth of the flu fatalities that Philadelphia saw. But if St. Louis had waited another week or two to act, it might have suffered a fate similar to Philadelphia’s, the researchers concluded. By the end of the flu season the next spring, St. Louis had counted 31,500 illnesses and 1,703 deaths.

These two curves above) have already played out in the U.S. in an earlier age — during the 1918 flu pandemic. Research has shown that the faster authorities move to implement the kinds of social distancing measures designed to slow the transmission of disease, the more lives were saved. And the history of two U.S. cities — Philadelphia and St. Louis — illustrates just how big a difference those measures can make.

- Have a comment? Send to: elliott@brack.net

Follow Us